Research

Explore my publications, the talks and conferences I participated in and my research interests.

Publications

32026› Numerical resolution of 2D nonlinear shallow-water equations with a partly immersed surface obstacle In preparation

22025› An high-order robust scheme for 2D nonlinear shallow water equations with topography and friction effects on unstructured grids Submitted to Journal of Computational Physics

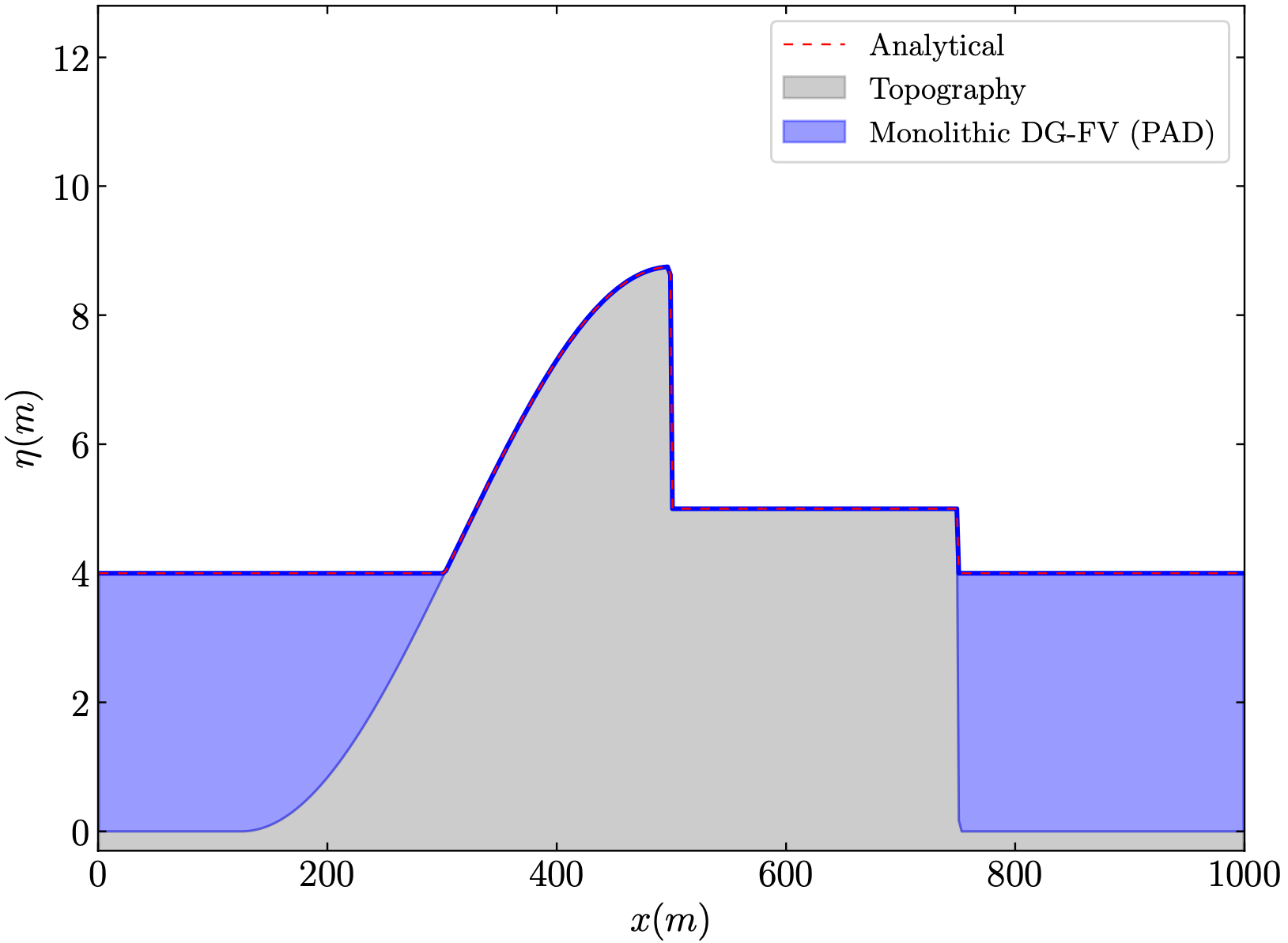

12025› Local subcell monolithic DG/FV methods for nonlinear shallow-water models with source terms Submitted to International Journal for Numerical Methods in Fluids

Talks & posters

Métiers des mathématiques - Conference given to bachelor’s and master’s students

Title. Modèles et méthodes numériques pour les interactions entre vagues et structures flottantes.

Location. Montpellier, France.

Date. 19/02/26.

[Slides]

ICOSAHOM - International Congress on Spectral and High Order Method

Title. Local subcell monolithic DG/FV scheme for NSW equations with source terms on unstructured grids.

Location. Montréal, Canada.

Date. 14/07/25.

[Slides]

MIPS Colloquia - Semaine du pôle Mathématiques, Informatique, Physique, Systèmes

Title. Designing numerical methods for free-surface flows towards reliable wave-structure interactions.

Location. Montpellier, France.

Date. 02/06/25.

[Slides]

CIMAV - Congrès Interdisciplinaire sur les Modèles Avancés de Vagues

Title. An high-order robust DG/FV scheme for nonlinear shallow water equations with source terms on unstructured grids.

Location. Aussois, France.

Date. 13/05/25.

[Slides]

Ph.D. Day - Séminaire des Doctorants

Title. Monolithic DG/FV schemes on 1D nonlinear shallow water equations.

Location. Montpellier, France.

Date. 15/03/24.

[Poster]

Introduction to newcomers - Séminaire des Doctorants

Title. Modeling, solving & implementing PDEs from waves-structure interactions.

Location. Montpellier, France.

Date. 25/10/23.

[Slides]

Research statement

My research lies at the intersection of mathematical modeling, numerical analysis, and the study of partial differential equations (PDEs) describing fluid flows. In particular, during my PhD, I focused on nonlinear systems of hyperbolic balance laws, which are used to model the evolution of quantities that are transported and conserved in time. These systems take the general form

where $\mathbf{U}$ represents the vector of conserved variables (our unknowns), $\mathbb{F}$ the flux function that can be nonlinear, and $\mathbf{S}$ possible source terms arising from geometry, external forces, or coupling effects. The mathematical challenge is that even smooth initial data can generate discontinuities in finite time, which makes the analytical study of such systems extremely delicate. Because of the lack of regularity of weak solutions, only partial theoretical results are available, and the numerical approximation of these phenomena must often combine high-order accuracy with stability and robustness.

Among the many examples of such systems, the nonlinear shallow-water equations (NSW) play a central role in the water wave community; they provide an asymptotic model derived from the incompressible Euler equations under the assumption of small aspect ratio (the depth of the fluid is much smaller than the horizontal scale). Despite their asymptotic nature, the shallow water equations remain extremely valuable in practice. They provide an accurate description of the main physical mechanisms governing free-surface flows, while avoiding the prohibitive computational cost associated with solving the fully three-dimensional Euler or Navier–Stokes equations. They thus offer an effective compromise between physical realism and numerical efficiency. Even though they do not account for dispersive effects (captured in more refined models such as the Boussinesq or Green–Naghdi systems), they remain one of the most widely used and robust approximations for practical flow simulations. Given a smooth parameterization $b$ of the bathymetry variation, the NSW equations read as

with $\mathbf{v} = (\eta,\mathbf{q})^t$, where $\eta$ is water total elevation, $\mathbf{q}$ is the horizontal discharge, and $\mathbf{S}[b](\mathbf{v})$ is a generic source term that may contains topography, friction and/or Coriolis effects.

From a numerical viewpoint, however, their discretization poses several challenges. Capturing both smooth solutions and discontinuities requires schemes that are stable in the presence of shocks, preserve the positivity of the water height ($i.e.$ ensuring at the discrete level that $H\geq0$), and maintain steady states such as the so-called “lake-at-rest” equilibrium. Moreover, in many realistic configurations, the flow interacts with complex geometries, obstacles, or moving boundaries, which demands robust and flexible numerical frameworks.

New high-order numerical frameworks for shallow water asymptotics

In the numerical analysis of nonlinear shallow water models, two main families of methods coexist. On one hand, classical finite volume (FV) schemes are extremely robust: they are able to handle naturally shocks, dry areas, and abrupt variations of topography without breaking down. However, they usually provide initially low-order accuracy and tend to be too diffusive. On the other hand, finite element methods, in particular discontinuous Galerkin (DG) formulations, can reach arbitrarily high orders of precision and are well-suited for complex geometries, but they are much more sensitive to numerical instabilities and require additional stabilization mechanisms to ensure robustness.

The numerical strategy I have developed aims at combining the best of both worlds within a single and consistent framework. Building on a method initially introduced by my advisor François Vilar, we reformulated the computational domain by subdividing each mesh element into subcells and allowing both FV and DG representations to coexist locally, making it possible to merge two normally incompatible paradigms within a unified structure. Through a convex blending between the finite volume contributions (responsible for robustness) and the high-order DG ones (responsible for accuracy), the method dynamically adapts to the local regularity of the solution. It ensures that the scheme remains positivity-preserving, stable around steady states, and accurate in smooth regions.

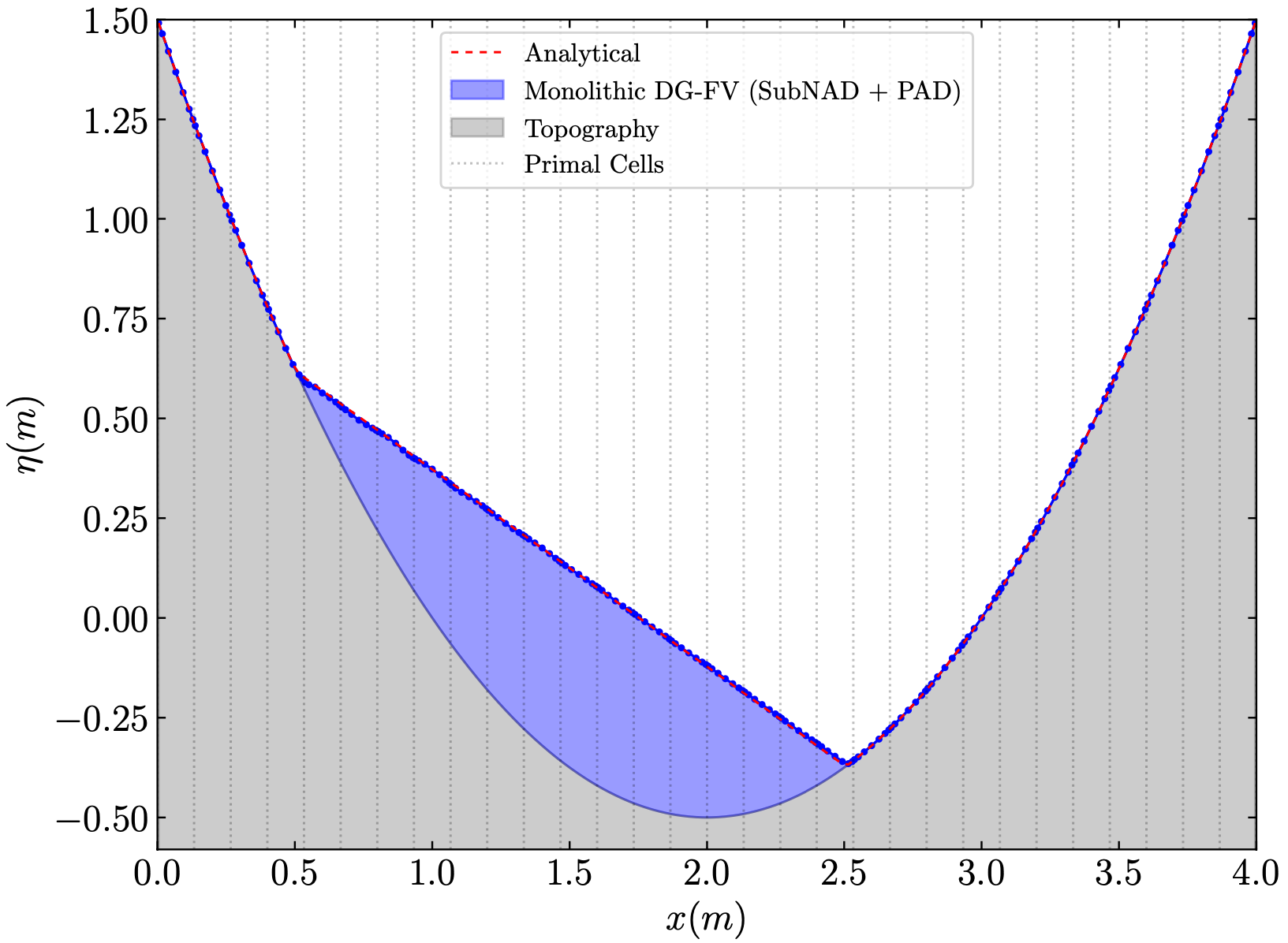

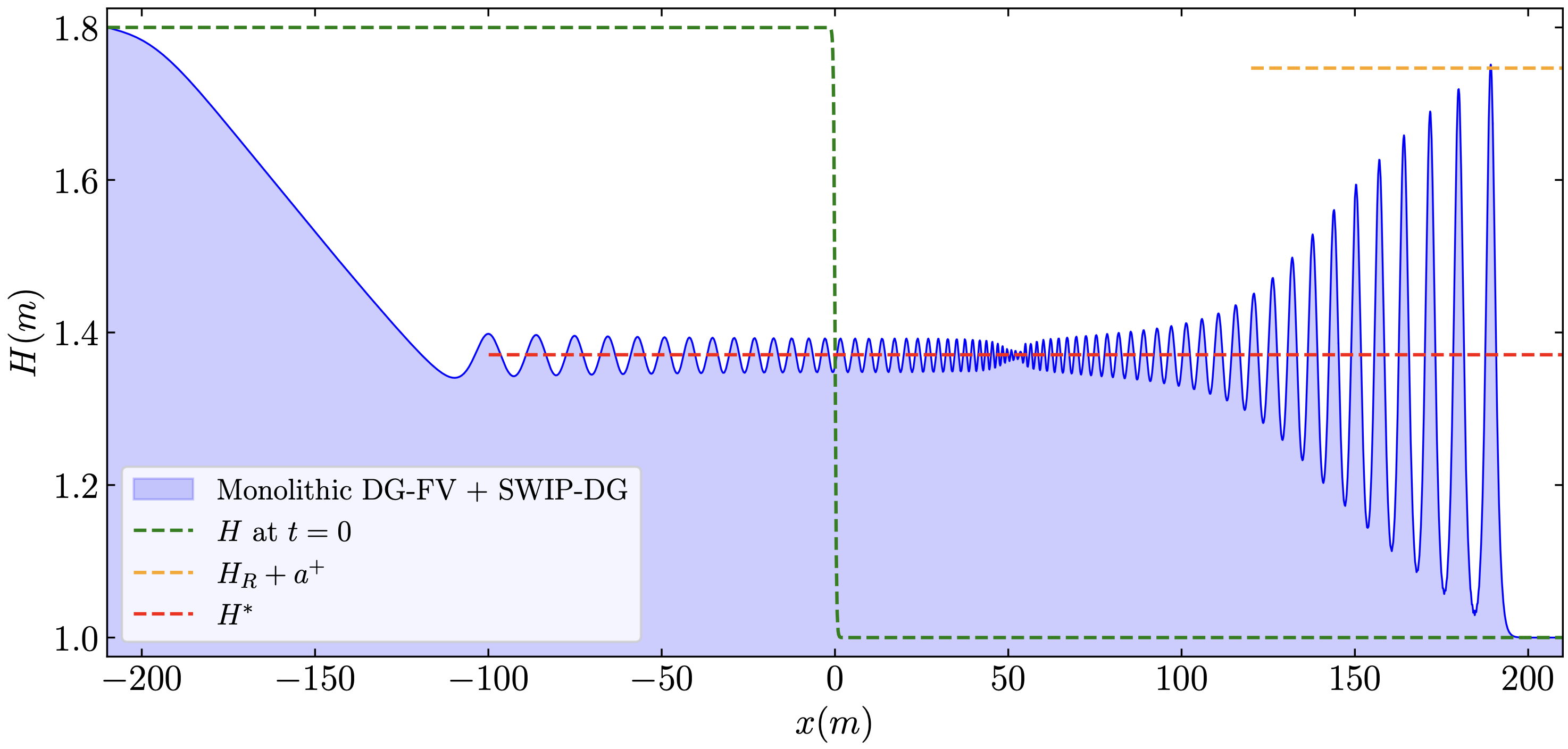

This framework was first developed and analyzed in the one-dimensional setting, in a work focusing on the construction of the method and on the preservation of some key theoretical properties. In this first article, we also proposed a natural extension of the approach to the Green–Naghdi equations, which form a dispersive correction to the NSW system. Indeed, in that setting, the dispersive effects are reformulated as an auxiliary elliptic problem that introduces an additional source term in the NSW equations. One of the main strengths of the proposed framework lies precisely in the treatment of such source terms: the method handles them in a consistent and unified way, without the need for additional numerical artifacts. The elliptic part is solved using a SWIP-DG (Symmetric Weighted Interior Penalty Discontinuous Galerkin) method, ensuring stability and precision. This coupling strategy yields a high-order dispersive model capable of capturing Green–Naghdi-type solutions with excellent accuracy and stability, while preserving the simplicity and robustness of the shallow water solver.

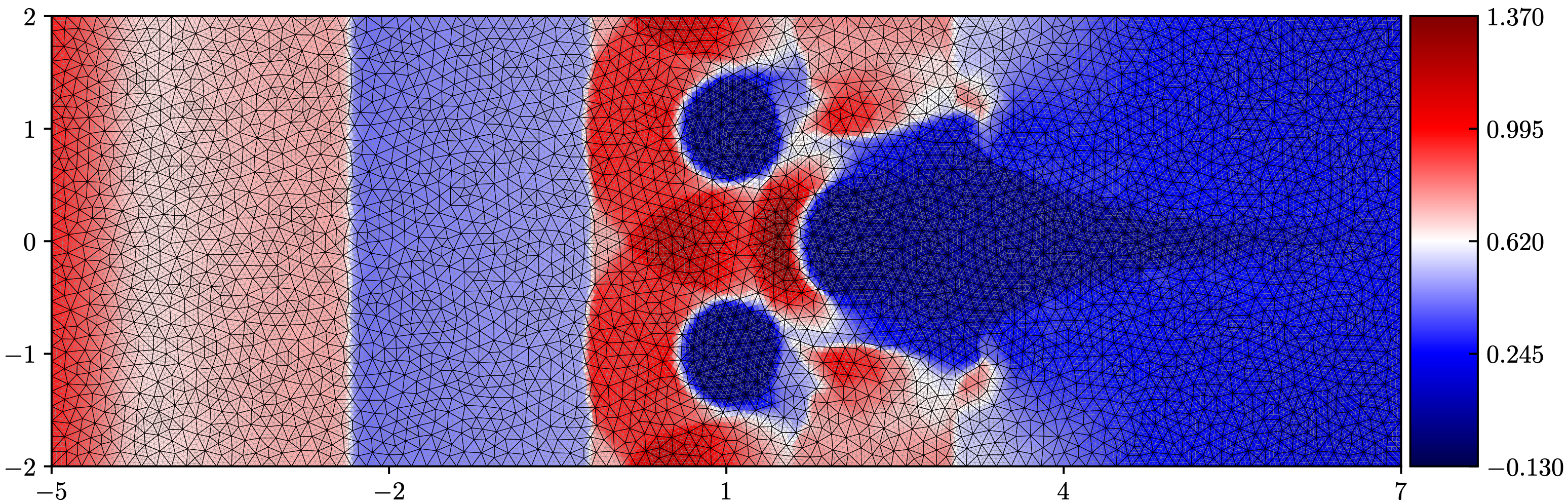

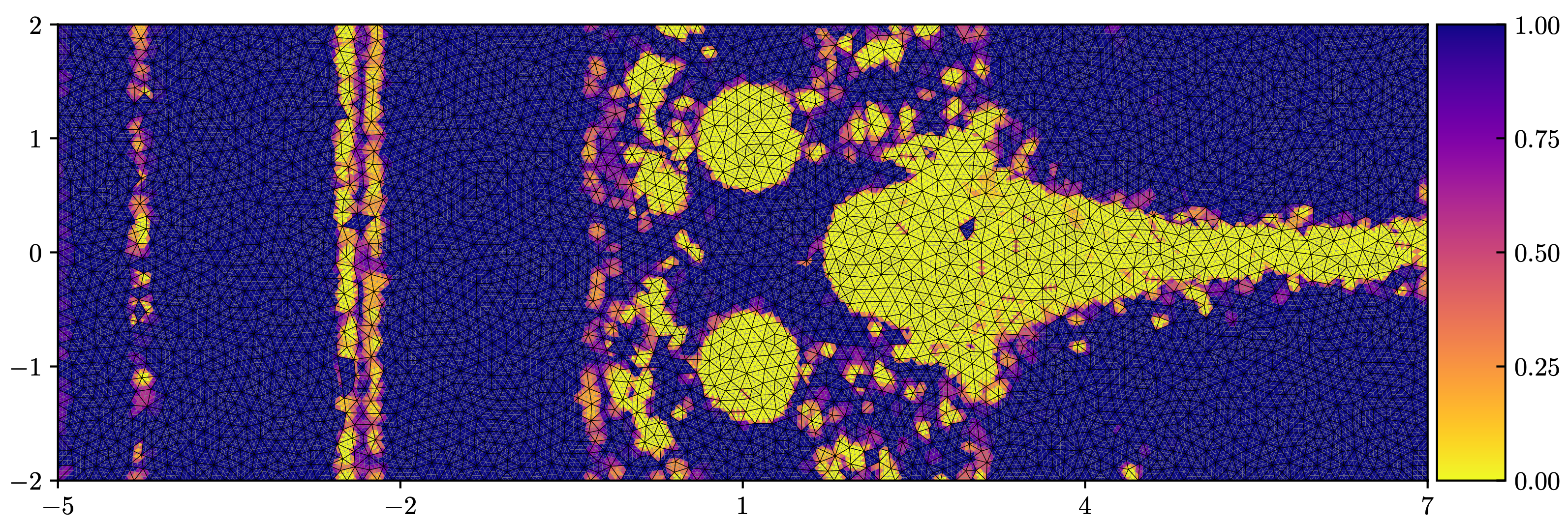

More recently, this monolithic approach has been extended to two-dimensional unstructured meshes. The extension of the framework to two-dimensional configurations represents a major step forward, both technically and theoretically. The proposed formulation successfully addresses these difficulties and exhibits excellent numerical properties: it achieves high-order accuracy even on coarse and highly irregular meshes, while maintaining robustness in the presence of complex bathymetries, dry fronts and challenging benchmarks. These results confirm the versatility and efficiency of the approach, making it a promising tool for large-scale realistic simulations of shallow water flows.

Floating structures in shallow water regimes

The increasing demand for renewable marine energy has motivated the study of floating devices capable of converting wave motion into electricity. From a mathematical viewpoint, these systems involve complex fluid–structure interactions, where the dynamics of a floating body must be coupled with the free-surface flow. In collaboration with David Lannes, we are developing a unified theoretical and numerical framework to describe such interactions within an asymptotic shallow-water regime, aiming for both mathematical consistency and computational efficiency.

The resulting model combines three complementary components: a hyperbolic system governing the exterior flow (the nonlinear shallow-water equations), a set of ordinary differential equations, and an elliptic problem describing the internal pressure distribution. Building a stable and accurate solver for this coupled system requires treating these components within a single, coherent formulation that preserves the main physical and mathematical invariants.

To achieve this, we rely on the DG/FV framework introduced in the previous section for the hyperbolic part, and on advanced discretizations for the elliptic component based on Hybrid High-Order (HHO) methods, which are finite-element-like schemes combining cell and face unknowns to achieve high-order accuracy while retaining local conservation, computational efficiency and flexibility on very general meshes. This ongoing work constitutes the third main contribution of my thesis. It provides a mathematically well-posed and numerically efficient framework for the simulation of wave–structure interactions in shallow-water regimes, with potential applications to the study and optimization of wave energy converters and other floating systems relevant to renewable marine technologies.